While news headlines are saturated with political unrest, wars to unravel, and terrorism, the world doesn’t suspect that a microscopic enemy could cause as much damage as thousands of deaths every year. This microscopic enemy is a multidrug resistant bacteria or as many of us call them, superbugs. Recognizing this continuously growing antibiotic resistance as an increasing threat to modern healthcare, WHO has proclaimed this week (November 12-18th) to be the World Antibiotic Awareness Week.

Almost a century ago, Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, which was later introduced as a treatment for infections. The development of mass-produced antibiotics soon flourished over the next decades until it hit plateau in the 1950s and the latest new class of antibiotics to reach clinical stage was discovered in late 1980s.1 Although the innovation/development of antibiotics dramatically slowed down, the use of antibiotics did not; and people were using antibiotics for many applications, including the treatment of bacterial infections or to make livestock grow faster in crowded and unsanitary environments. As a result, the over- or misuse of antibiotics lead to the faster development of resistant bacteria, which at first, was easily treated by changing to another type of antibiotic. However, this became a major problem when some bacteria started to become resistant against many different types of antibiotics.

The fact that the problem of superbugs is increasing is an alarming situation as infectious diseases can be easily spread, and the lack of efficient treatment options leaves us out of ammunition to stop superbugs from spreading and harming innocent lives.

The field of antibiotic development against superbugs is messy – on one side, we have a huge unmet need for more effective treatments and on the other side, we have industry actors who are not motivated to innovate.

Why is discovery of new classes of antibiotics so low?

The simple answer is that discovery of novel antibiotics is difficult, there is a lack of incentives for drug development companies, and the business case is trivial. To start, some antibiotics have been traditionally discovered by screening natural compounds (e.g. found in different soils) and in few cases by testing synthesized compounds against bacterial cultures. This is a time consuming and costly trial and error process. Thus, the biopharmaceutical industry opts for creating analogues of existing antibiotics as this pathway is not as costly and risky (e.g. lower toxicity profile).

The development of novel antibiotics has several CONS that turns drug development companies towards the opposite direction. As seen on table 1, it can be determined that the outcome of developing novel antibiotics does not make up for the high risks, costs and long time that it takes to develop novel drugs. As you can see, antibiotics with a novel class or mechanism of action, risk being placed in reserve and consequently, risk having lower market penetration and lower exclusivity time in the market (e.g. due to fixed patent lifetime). This is a problem that Big Pharma, federal governments as well as regulatory agencies have recognized. While several Big Pharma companies have decided to leave this space, the government and regulatory agencies have stayed to create initiatives to work on the alarming problem of superbugs.

Table 1. Pros and cons for biopharma to develop antibiotics for multidrug-resistant bacteria

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

What are regulators doing to incentivize the development of antibiotics?

Under the GAIN act, the FDA began granting Qualified Infectious Disease Products (QIDP) designations in an attempt to incentivize the development of antibiotics. Some of the incentives under this act include the following:2

- Additional 5 years of exclusivity

- Fast -Track designation

- Priority review status

- Federal funding/grants

According to the FDA, 5 years since the GAIN act was passed, approximately 147 drugs were granted QIDP designation. Of these drugs, 74 were considered novel and 12 were approved.3 However, deeper analysis indicates that many of the drugs with QIDP designation involve improvements of existing drugs with new dosages and new indications. Only a few products addressed the unmet need of new classes of antibiotics or drugs with new mechanisms of action.4

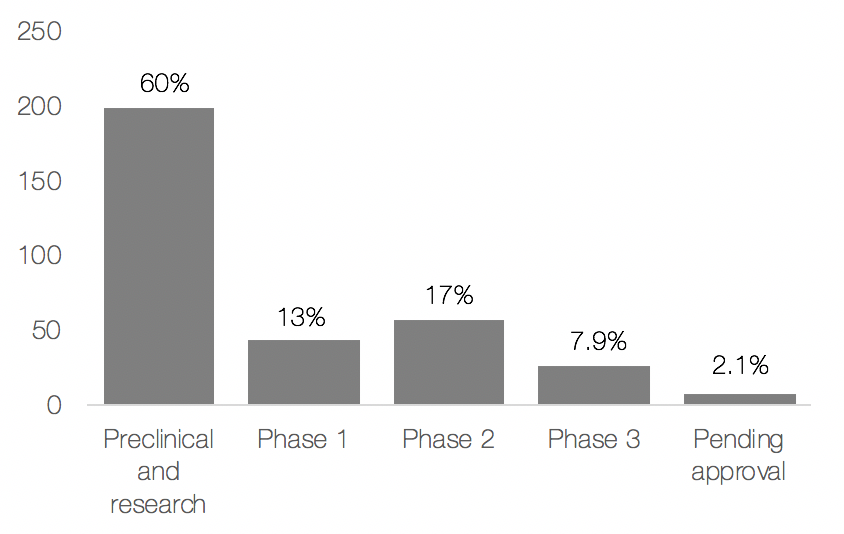

Further analysis of the antibiotic development pipeline was performed using Medtrack where the results are illustrated in Figure 1 and 2. Overall, there is a large increase of candidates entering the antibiotic space. As seen in Figure 1, 60% of the candidates are in preclinical stage, thus indicating that many new candidates are being developed. Deeper analysis indicated that 47% (161/330) of the developed antibiotics are classified as novel, however, only 3.8% (13/330) of the antibiotics were from a new class of antibiotics or had a new mechanism of action.

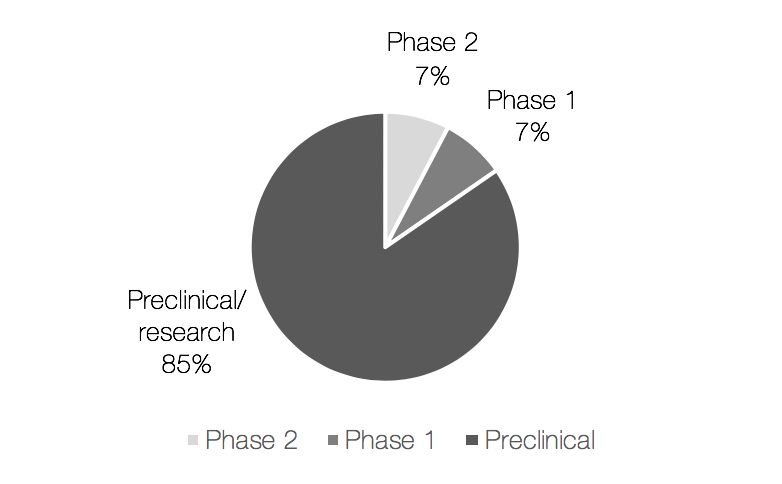

Most of the candidates from a new class or with new mechanism of action were in preclinical stage (Figure 2), except for Lytixar™ (Ltx90) and SGX942, that were in clinical development stage. Lytixar™, developed by Lytix Biopharma is in phase 2a for staphylococcal infections, however, no recent development since this trial has been reported. Following is SGX942 developed by Soligenix, which is in preclinical/phase 1 for bacterial infections and in phase 3 for the treatment of mucositis in head and neck cancer patients receiving chemotherapy.

Based on this analysis, it can be determined that the development of antibiotics has indeed increased by volume, however current regulatory incentives do not seem to be enough to encourage the development of new classes of antibiotics or those with new mechanisms of action. To make matters worse, most of these candidates are mainly in preclinical phase – where the rate of success is very low and the time to market is long.

Figure 1. Candidates in the antibiotic development pipeline

Figure 2. Antibiotics that belong to a new class of drug or have a new mechanism of action

Concluding thoughts

The field of antibiotic development against superbugs is messy – on one side, we have a huge unmet need for more effective treatments and on the other side, we have industry actors who are not motivated to innovate. Despite the efforts in introducing the GAIN act, the results have been in the middle-of-the-road and companies have mainly focused in developing better analogues of existing classes of antibiotics. Little is seen on the development of antibiotics from new classes or mechanisms of action – which are essential to fight superbugs. This could be a sign that soft funds should be highly allocated to the discovery and translation of new classes of antibiotics or mechanisms of action to fight superbugs. Also, regulatory incentives should be fitted more to incentivize antibiotics from new classes of antibiotics or with new mechanisms of action. Although, the GAIN act has only been active for more than 5 years, more time is required to see the real impact of this legislation in the development of antibiotics. However, this doesn’t mean that this act cannot be amended to accommodate what is really needed, which is the development of antibiotics from new classes or new mechanisms of action. A historically-relevant example is the Orphan Drug Act passed in 1983. This act incentivized drug development companies to focus on rare diseases that were once neglected by the market. The passing of this act was successful as the development of orphan drugs has increased dramatically and similar regulations have been incorporated in other countries. Just to illustrate its success, more than 27% (60/220) of the approved drugs in 2017 had orphan drug designation. Thus, similar to the Orphan Drug Act, we hope that the GAIN act can incentivize drug development companies to innovate in ways to fight against superbugs.

By: Paola Jo, Senior Business Analyst

References

- ReAct (n.d.) Few antibiotics under development [Available online] https://www.reactgroup.org/toolbox/understand/how-did-we-end-up-here/few-antibiotics-under-development/ (Accessed July 27, 2018)

- Jungman, E. (2018) FDA Releases Draft Guidance on Antibiotic Policies under the GAIN Act. PEW [Available online] http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2018/04/20/fda-releases-draft-guidance-on-antibiotic-policies-under-the-gain-act (Accessed: July 25, 2018)

- Department of Health and Human Services (n.d.) GENERATING ANTIBIOTIC INCENTIVES NOW Required by Section 805 of the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act Public Law 112-144. [Available online] https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/UCM595188.pdf (Accessed July 25, 2018)

- Simpkin, V., Renwick, M., Kelly, R., Mossialos, E. (2017) Incentivising innovation in antibiotic drug discovery and development: progress, challenges and next steps. The Journal of Antibiotics 70: 1087 – 1096