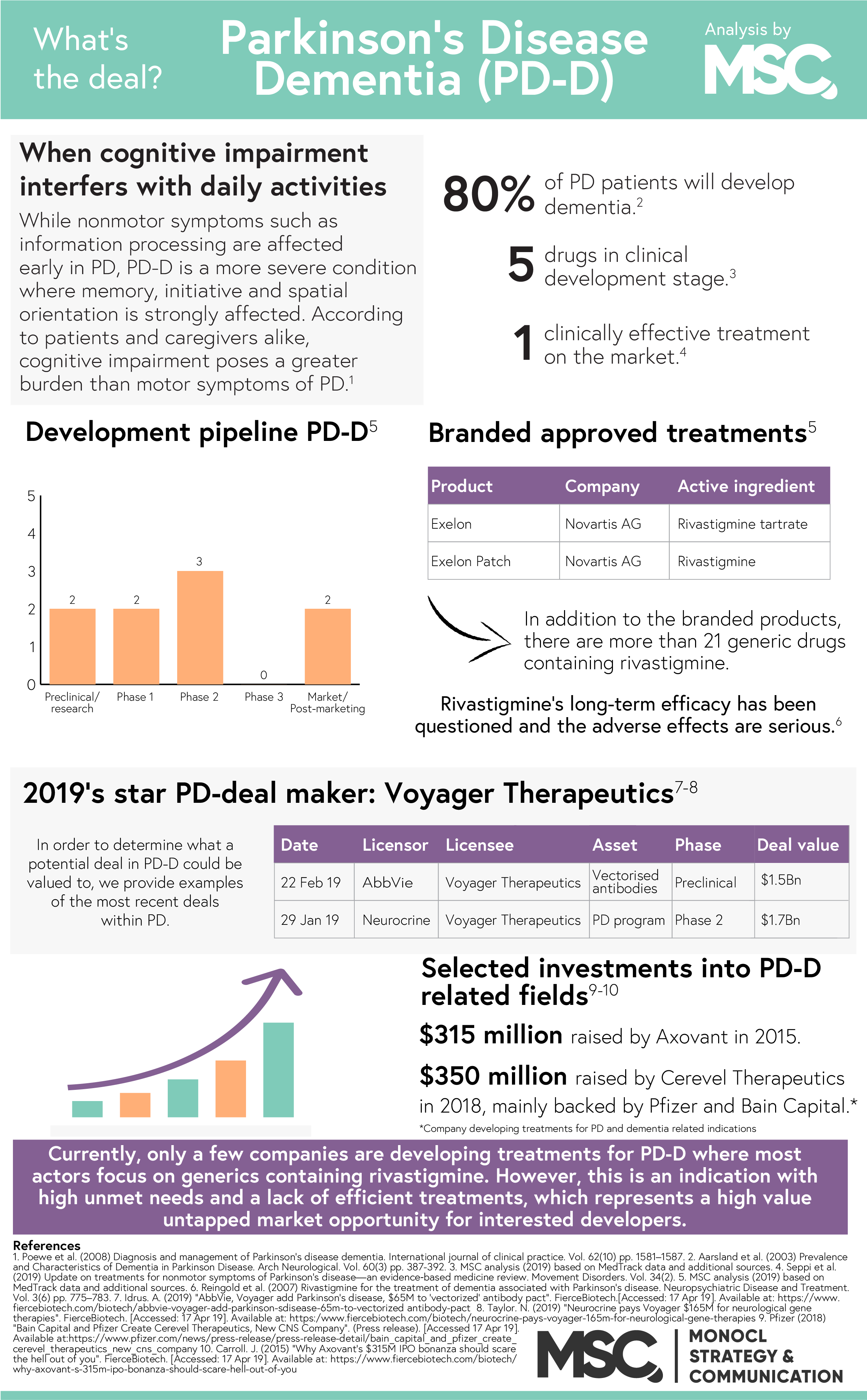

Every year, 1% of the population over 60 years of age are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and it is estimated that more than 6.2 million people are living with the condition worldwide. During April each year, the Parkinson’s Foundation and similar organizations around the world work hard to highlight the disease and raise awareness of how life can be improved for Parkinson’s patients. While the condition itself is a source of disability and hardship, people who progress to develop Parkinson’s disease dementia experience a significantly lower quality of life, as well as a much higher morbidity than other patients. The need for treatment is urgent, so we took a look at the status quo and asked: what’s the deal with Parkinson’s disease dementia?

Neurological disorders – diseases of the brain, spine and the nerves, are now the leading cause of disability in the world. Of these disorders, Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the fastest growing with an estimated population of 14.2 million patients in 2040. In PD, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases, the degeneration of nerve cells eventually affects the cerebral cortex. When this happens, the transmission of information between neurons (neurotransmission) is impaired, resulting in a number of motor, cognitive and psychiatric symptoms. One of the most debilitating comorbidities in is dementia and over time, a staggering 78.2% of these patients will develop Parkinson’s disease dementia (PD-D).

Diagnosing PD-D

While cognitive symptoms are affected early in PD, it is first when these symptoms become severe enough to affect normal functioning that PD-D can be diagnosed. Typically, PD-D primarily affects the patient’s ability to maintain attention, his or her memory, executive functions and visuo-spatial orientation. For the patient and caregiver alike, these cognitive impairments are often perceived as extremely stressful. Over time, as the condition progress, the patient may no longer be able to initiate tasks, maintain conversations or remember friends and family. In addition to the primary symptoms, the patient may also experience hallucinations and strong emotional changes. Often, PD-D has a larger negative impact on both the caregiver’s and patient’s quality of life than the physical symptoms of .

Current treatment for PD-D is symptomatic, modest, and only transiently effective.

Currently available treatments

In 2011, Caviness et al. concluded that the current treatment for PD-D is “…symptomatic, modest, and only transiently effective. There is a wide agreement that more effective treatment is needed”. Since then, little has happened. In January 2019, a group of researchers provided an update on treatments for non-motor symptoms of PD and found that rivastigmine is the only clinically validated treatment for the disease. Unfortunately, rivastigmine only offers a modest benefit to the patient due to the combination of a modest long-term efficacy and cholinergic adverse effects. In addition to rivastigmine, some Alzheimer’s disease treatments such as donepezil and galantamine have shown potential in treating PD-D but lacks the clinical evidence to prove their efficacy. The 2019 study thus deemed donepezil and galantamine “possibly useful”, awaiting further clinical research.

The future of the field

Today, only a handful of companies are conducting clinical research within PD-D. Instead, the industry trend is to develop drug candidates the bigger markets dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease and later evaluate these candidates for PD-D as well. The reason behind this approach is that both Alzheimer’s disease and PD-D are associated with marked cholinergic deficits. However, increasing the scope of a candidate to include PD-D in addition to Alzheimer’s isn’t entirely smooth as the deficiency is greater in PD-D.

In summary, the need of continued research into new and better treatments tailored for PD is high. This specifically regard treatments that can address key disease mechanisms or has the potential to prevent or delay PD patients from progressing to PD-D. This need will only grow bigger over time in our ageing society.