As a medical device company, you have surely already prepared for the upcoming date of application for the new European Union Medical Device Regulation (MDR) on May 26, 2020. On the surface, it might seem like just another regulatory overhaul. It is, however, both a reaction to some significant flaws in the medical device product life cycle, as well as an opportunity provider for businesses to improve efficiency and product quality. Ultimately, the aim is vastly improved patient outcomes. We were curious to paint a picture of the factors driving these changes and discuss the future of the medical device industry as a result of these new regulations.

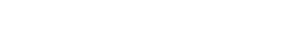

MDR is essentially a merge between the Active Implantable Medical Device (AIMD) directive and the Medical Devices Directive (MDD), while the new In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) is an update of the In Vitro Diagnostic Devices Directive (IVDD). The new medical device regulation (MDR) will begin its reign on May 26, 2020, but companies that have been issued an EU declaration of conformity (EC) before this date of application will be able to sell or distribute devices that were certified under the previous the MDD or IVD. IVDR, which focuses on in vitro diagnostics, has many similar implications to MDR as well as several compliance deadlines that coincide.

Key timeline by the Regulatory and Clinical Research Institute

The changes in the new regulation will affect different actors in different magnitudes, but one certainty is that as a medical device company (no matter what part of the value chain), these changes cannot be ignored.

The purpose of MDR

The purpose of the new regulations is to improve directive harmonization, improve user and patient safety, improve product traceability, quality assurance, and transparency, as well as to provide fair market access for manufacturers. These new regulations have several exciting implications for supporting markets. Companies should, however, look to their trusted legal expertise for more information about the nitty-gritty details.

The catalyzers of MDR

There have been quite a few large medical device scandals that were implied to be the catalyzers for these European medical device regulatory changes. One of the main issues lying at the core of these scandals is the sale and distribution of counterfeit products that have made their way into the supply chain of medical devices, either as a replacement of the entire authentic device or its constituents. In general, it is estimated that 8-10% of all medical devices are of fake origin. This ties into suboptimal traceability, which is one of the key changes that MDR will address through the introduction of Unique Device Identification (UDI). UDI will hopefully also have a positive effect on recall costs, which can be as high as $600 million for a single product, not including the expensive lawsuits that might follow.

Breast implant scandal

One of the more significant cases credited to have been a part of triggering the initiative towards tighter medical device regulations is a breast implant scandal that caught the attention of regulatory authorities. Company Poly Implant Prothese (PIP), a French company launched in 1991, produced approximately two million sets of silicone breast implants over the course of 20 years. The problem began when the company started producing implants made from cheaper industrial-grade silicone that was not approved for medical use. These implants were rupturing at a rate double that of the industry average, causing dire patient consequences. In 2011, the French government recommended that 30,000 women with PIP implants get them removed, and in 2013 the founder of the company was sent to prison for four years in addition to receiving a lifetime ban from working within the medical device sector.

Vaginal mesh device

Another medical device scandal with tragic consequences involved a vaginal mesh device, which was first introduced in the 1990s and used for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), two common complications after childbirth. The vaginal mesh led to complications that have severely altered women’s lives, including nerve damage, chronic pain, and several reported deaths. Researchers currently estimate that these issues occurred in between 15–25% of patients with the device. The implants were formally introduced in the US in 1996 for SUI and 2002 for POP, but the first FDA warnings got issued in 2008. Since then, several lawsuits have taken place in the US, Australia, and New Zealand. In 2017, it was revealed that the mesh manufacturers had failed to adequately warn UK doctors of the risks associated with the mesh and had inadequately tested the kits before selling them. A year later, it turned out a supplier had used untested counterfeit plastic in its mesh products.

Final thoughts

The new regulations might seem straight forward and targeted towards certain company functions at a glance, but the entire holistic operations of medical device companies will need to change. Cross-functional teams will need to share even more information than ever before. Every product, whether new or old, will be looked at as a brand-new device.

As discussed in an interview with Caroline Byrd, a Director of Regulatory Affairs at Abbot, companies might need to revise their entire strategy and think about factors like design improvement needs, post-market surveillance activities, and the management of the product life cycle from the very beginning of the product development phase. Thus, there is a very realistic chance that the operations of a medical device company need to change holistically for survival.

We want to think that we can predict the industry impact of these new regulations, but the fact remains that it is impossible to foresee all of the implications such an extensive regulatory overhaul. It would, however, be naïve to say these changes won’t bring upon us novel business opportunities.

By: Robert Ljungberg, Associate at MSC